- ________________________________________________________________________________________

- Last modified 10/07/08

- Copyright © by Nila Gaede 2008

1.0 The service economy produces neither wealth nor children

In his book, The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State, [1] Friedrich Engels explains that once the communistic

society is in place and economic equality is attained, humans would finally settle down to essentially monogamous lifestyles

founded on love rather than on wealth and live happily ever after. Perhaps he yearned for a day when people would not be

pressured into unholy marriages by economic forces and social caste.

Both of these noble goals are wishful thinking. Not only will economic equality never come about as Engels envisioned, but

the correct trend is the total destruction and phasing out of all types of marriages. The patriarchal family of the agricultural

age gave way to the nuclear family of the manufacturing period which has recently shifted to a service economy represented

by single parents and bachelors. There is no room for children in an urban society. Without children, there is no future for

the human race.

So how does scarcity (economics) manage to steer the evolution of the family towards childless bachelors?

Orthodoxy has for some time maintained that large families are a result of ignorance and poverty. [2] We instinctively

associate high fertility with a nation’s backwardness. The vision that comes to mind is a destitute African woman holding

in her arms several famished kids with bloated bellies. We have been conditioned to believe that only a poor, uneducated

woman allows herself to get pregnant ten or fifteen times.

However, the European experience tells a different story. The population in the old continent expanded in the 19th Century

during the Industrial Revolution, a period in which wealth increased and the middle class expanded. Therefore, high fertility

does not necessarily have an inverse relation with the quantity of material goods in circulation (i.e., poverty) as orthodoxy

would lead you to believe. Quite the contrary! The demographic and economic history of Europe shows that tangible goods

go hand in hand with population.

Indeed, an intuitive review of how population relates to the quantity of goods in circulation should lead us to conclude that

they are directly proportional. Assume you travel to the distant past, say, to the Mayan Civilization. How would you estimate

the number of inhabitants in the Mayan heyday? Would you determine this by the number of barbers, dancers, or priests

that they had? Or assume that you traveled to another planet to find that human-like beings went extinct long ago. You

discover in a rusty computer somewhere that there were 10 insurance companies insuring people for a total value of

1 trillion dollars and that the 10 banks that operated had deposits for a total of 5 trillion dollars. What would this tell you

about total population? How much was a dollar worth? Just consider what would happen today if I wave my magic wand

and double the money in circulation in the U.S.? What would that tell us about its population?

The point that I am trying to make with these examples is that the service sector is not a reliable demographic yardstick.

We can generate and maintain millions of more bank accounts with the same companies we have today and with more

or less the same personnel. If I told you that the Mayans had a hundred priests, this would not give you an idea of what

their total population was. One priest can service 10 as well as 100 parishioners. One TV station can broadcast to millions

or to billions. One politician can represent thousands or millions. Conversely, if you went to a planet were life went extinct

long ago and you collect a total of 1 billion cell phones from the ground, you would not conclude that this was a tiny

colony of 100 individuals. A colony of 100 men has no ability to use a million TV sets or a million beds. It is the level of

tangible goods that gives us an indication of total population and not the level of abstract services.

Only two of the segments of Man’s artificial economy produce tangible goods: agriculture and manufacturing. Services

certainly do not. Manufacturing delivers nouns. The service sector provides verbs. I will use the words wealthy or wealth

to refer to the possession of a tangible product. I will use the words rich or richness in the context of an abstract good

(e.g., money) or of a service, whether actual or potential. I will not include land within wealth because this is simply an

abstract division of something that remains constant. The land was already there before any of us came on board; we

did not create it. Humans merely parcel out existing land to particular individuals based on arbitrary criteria. Therefore,

if you own a house, a yacht, and a cell phone you are wealthy. If you have a bus ticket and a lot of cash, and can buy

the services of a prostitute or that of the electric company, you are rich. If you inherit a stunning castle on the Rhine,

but are penniless, you are wealthy, but not rich. If all you own is a bunch of gold coins valued at $100 million, you are

rich but not wealthy. Of course, the current economic environment allows you to sell the castle and become rich or

exchange the coins for a castle and become wealthy.

Manufacturing contributes to wealth: it produces a physical product. The more products you have, the wealthier you

are. Services contribute to richness. When the barber shaves you, he has performed a service and become richer.

You transferred money from your account to pay for his services. This is simply an accounting transaction. The barber

does not have a physical object to show for his efforts, and this becomes evident when we do inventory. I wave my

magic wand and make all the money in the world disappear at this very moment, including checking, savings, credit,

stocks, and bonds. The barber may not have too much trouble convincing the jurors that he owns the TV he has in

his apartment. He will have very little luck persuading them that he owns the shave you just walked off with. Likewise,

if I destroy all the information in the world in a single swipe, all the checking and credit accounts vanish. You are

suddenly worth as much as what you have in the form of tangible assets. Money doesn’t have an intrinsic value like

a bicycle or a chicken.

Global fertility seems to follow the trends of manufacturing and not of services. The greater the proportion of GDP

that the service sector takes up, the fewer children we put out. The history of 19th Century Europe also followed

this trend. Population increased geometrically in proportion to wealth (tangible goods). Food kept pace with

population. Today, the global population is still rising, but it is doing so at a slower rate. Predictably, wealth (the

number of tangible goods) is still increasing worldwide, but at a slower rate. For all practical purposes, this

symbiotic relationship between material goods and population can also be seen in reverse. The day you constrain

real wealth (goods), you can expect fertility to decline as well. The decline in global fertility as a function of the

overall decline in manufacturing can be seen in this light.

If we concede that fertility goes hand in hand with wealth (i.e., manufacturing) as opposed to richness, we must

conclude that services have little to no chance of triggering a fertility spike comparable to what manufacturing

did in the 19th Century. The decline in manufacturing and a shift to services is a sign that we are no longer

accumulating wealth. If anything, we are just becoming richer:

- " It’s hard to imagine how service-sector expansion can play a role in wealth

creation… Currently, growth in service jobs appears to be increasingly

dependent on government spending, a connection not normally correlated

with sustainable wealth creation." [3]

If the decision of woman to have a family is based on authentic wealth, the decline of manufacturing presages

fewer and less numerous families. The macro-trend from large agricultural clans first to the industrial nuclear

family, then to proletarian single mothers, and finally to childless bachelors was already in the cards. Those

economists and demographers who argue that women have the option of reproducing again in the future have

no idea what they’re talking about. Assuming we grant this hypothesis, it first destroys the constant population

hypothesis. The economists cannot maintain these mutually exclusive arguments simultaneously. Either we will

attain ZPG and oscillate forevermore around a constant global population or we will continue to expand forever.

More importantly, the proponents have to show how a service economy would stimulate fertility in the first place.

Not only does the service economy have no need for labor in the long run, but the structure of the family unit is

moving in the direction of bachelorhood and childlessness. Therefore, what remains to be settled is whether our

artificial economy can be maintained by a population that oscillates around constant magnitude. If it can’t, we are

guaranteed to decline into extinction.

2.0 The ideal economy: exponential demand and no labor

What do contemporary businesses look for year after year?

In a natural economy, the end of the population explosion is a blessing. If the number of wildebeest and lions

would remain more or less constant and low enough to give the grasses time to recover, this state of affairs

could theoretically last forever.

In an artificial economy, on the other hand, a constant or declining population is a curse. Our ‘civilized’ economy

is founded on the concept of profit. Businesses look forward to increases in demand year after year, preferably

in an exponential mode. A company can make profits by selling more, by eliminating costs, or by putting out

new products. In practice, these goals are attained through a combination of technological or methodological

innovation or by reducing the labor force. The ideal business environment consists of an unlimited increase in

consumers paralleled by an unlimited decrease in labor. The perfect artificial economy consists of an entirely

mechanized labor force (robots) producing goods and services for an ever increasing pool of buyers (humans).

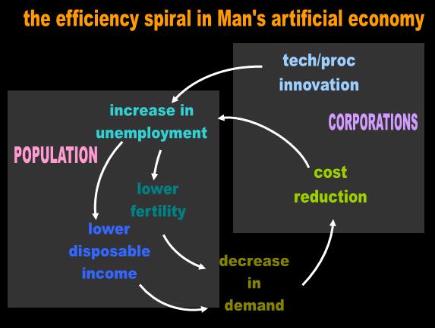

Unfortunately, our contemporary economy works in reverse. The more efficient corporations become through

technical or methodological innovation, the more they reduce labor. This part we have no trouble with. However,

as unemployment increases, disposable income decreases. A reduction in consumption leads to further layoffs

as competitors vie for a shrinking pie. Increases in unemployment also contribute to a decrease in fertility.

Nevertheless, a high fertility rate has no purpose in such an environment. Increases in unemployment coupled

with a reduction in birth rates contribute to further decreases in demand (Fig. 1). The entire spiral is self-sustaining

and exponential.

| Adapted for the Internet from: Why God Doesn't Exist |

| The robot in the suit will replace me at the office. The one on the left will help you around the house. And the one in the middle will be the father of your babies. |

| The service economy cannot be run on a constant population |

Note that these trends constitute a significant departure from the early days of manufacturing when more widgets

required more workers. The high fertility of the 19th and early 20th Centuries had a purpose. Today it doesn’t. Hence,

there is no incentive today for women to put out babies because these will not be absorbed as producers. As we all

know, until baby grows and can produce, she is just an expensive investment. She is all cost and no profit. In the

service phase of Man’s artificial economy both manufac-turing and services have little demand for workers and

employees, and the new generation is predictably frustrated that it cannot find jobs within these sectors. The bottle

neck is depressing fertility and constitutes a structural trend in our global economic development. This is not a

temporary phase within a business cycle as the relativistic economists would have you believe, but a terminal illness.

We never went back to agriculture or to hunter-gathering. Therefore, long-term economic history does not repeat itself.

Hence, assuming that the demographers at the U.N. are correct and implementation of family planning in third world

countries is responsible for curtailing fertility, the programs are working against the interests of our artificial economy.

Corporations absolutely need more consumers in the long run if they intend to stay in business. Without more humans,

there will not be profits. And without profits, corporations close their doors and our entire economy collapses. The day

that population comes to a halt, there is no purpose for corporations to hire people or to sell anything. In fact, the

economy runs into trouble much earlier, before projected ZPG occurs, meaning that ZPG also ends up occurring much

earlier than forecasted. An ideal, artificial economy running on a constant population is wishful thinking.

To recap, the global economy is gradually distancing itself from agriculture. Food is becoming an ever smaller

component of GDP and the labor force dedicated to this line item is disappearing. Yet food is all we need to stay alive.

Manufacturing is also dying. Day by day, firms are increasingly trimming their payrolls and shrinking by attrition.

Workers are increasingly being displaced towards service jobs or end up relying on the State. This is not a

phenomenon that affects only developed nations. This is a global megatrend.

The relativistic economist argues next that innovation and technology will keep manufacturing and service

businesses churning out new products. Humans will invent unimaginable gadgets that will catch the fancy of

future generations, and new manufacturing and service industries will continue to sprout until the end of time.

I reply that this vague proposal is an empty promise. We have invented all the relevant technology that we will ever

invent. Without revolutionary products and, more importantly, new categories of products, manufacturing will grind

to a halt. Then it doesn't matter anyways because manufacturing is a small percentage of the economy and getting

smaller by the day. We are so efficient and becoming even more efficient by the minute that we need ever fewer blue

collar workers to produce ever more goods of ever higher quality. In regards to services, there haven't been any new

service categories created in the last 50 years. In fact, labor intensive service categories such as telephone operator

and office clerks have been largely eliminated

Fig. 1 Paradox in our artificial economy |

Improvements in technology and

methodology lead to reductions in

labor. Unemployment leads to a fall

in demand and to a lower fertility

rate which in turn contributes further

to a fall in demand. Corporations

reduce costs in response to a fall in

demand by laying-off workers. Over

the long haul, the effect is to make

busi- nesses ever more efficient as

global population inches towards

ZPG. This process is not only

self-sustaining, but also exponential.

methodology lead to reductions in

labor. Unemployment leads to a fall

in demand and to a lower fertility

rate which in turn contributes further

to a fall in demand. Corporations

reduce costs in response to a fall in

demand by laying-off workers. Over

the long haul, the effect is to make

busi- nesses ever more efficient as

global population inches towards

ZPG. This process is not only

self-sustaining, but also exponential.

Module main page: The economic history of Man

Pages in this module:

- 1. This page: The service economy cannot be run on a constant population

2. The service sector has no ability to stimulate either fertility or the economy

3. The economy will collapse before we attain ZPG