- ________________________________________________________________________________________

- Last modified 09/27/08

- Copyright © by Nila Gaede 2008

| A mass extinction results when the ecological pyramid overturns |

| Adapted for the Internet from: Why God Doesn't Exist |

- 1.0 The definition of the term mass extinction

The traditional sense of the term ‘mass extinction’ is that a great percentage of species and entire families of animals

disappear in a geologically swift period of time.

- “ [A mass extinction] occurs when there is a sharp decrease in the number

of species in a relatively short period of time… a sharp drop in the rate of

speciation” [1]

Paleontologists infer mass extinctions from the bones they find in different layers of rock. Roughly, the thickness of a

layer is a measure of the length of a period and contains certain types of bones. If the paleontologists come across a

layer for which they cannot find certain types of animals that were quite prevalent in the previous layer, the conclusion

is that these animals disappeared at the boundary.

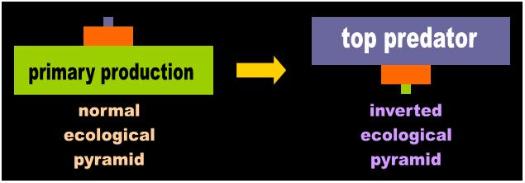

I prefer to define a mass extinction as one in which an entire food chain or several of them disappear. Thus, by definition,

the cause of a mass extinction has to do with economics. The carrying capacity for a specific food chain crashes and the

species that were members go down with it. This mechanism explains ‘a sharp drop in the rate of speciation’ (Fig. 1).

Meanwhile, a new generation of plants and animals are unaffected by what happens around them, which tends to explain

why mass extinctions are selective. If a local, background extinction has to do with aging, a global mass extinction has to

do with a wide-ranging economic collapse.

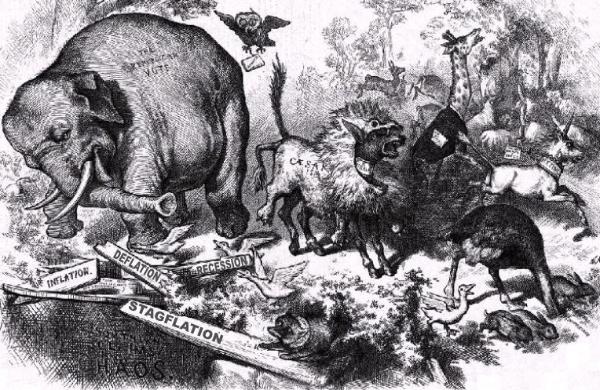

2.0 Wild economics: It’s a jungle out there!

If we define economics as the management of resources, the first thing we must come to terms with is that all species,

whether plant or animal, whether intentionally or unwittingly, practice some form of economics. All plants and animals

make use of resources in one way or another. Here are some examples:

- • Spatial resources: A gofer may dig a hole in the ground to build his burrow

- whereas a beaver collects wood to construct his shelter and a bird collects

twigs to build its nest. Ants also make holes in the ground and a colony of

termites constructs a mound. A crab may sleep under a rock.

• Reproduction: A stronger rat may crowd out weaker rats from sexual

- intercourse. A lion may challenge the reigning monarch, inherit the harem,

and kill the princes.

• Food: If primary production (e.g., pasture, phytoplankton) goes scarce in a

- region, the herbivores which are dependent on these resources (e.g., cattle,

zebras, zooplankton, fish) are now compelled to make involuntary choices.

The scarcity of prey, in turn, compels predators to vie for the remnants.

Again, whether these choices are conscious or result from instinct (whatever that is) is immaterial. The point is that scarce

resources lead to peculiar behaviors such as migration, infighting, and starvation. Prodded by necessity, every member of

a species scrambles to carve a niche for himself.

The most important economic resource managed by animals is food. Without food, nothing else matters. And here we have

no difficulty understanding Mother Nature’s fundamental law: all animals are ultimately dependent on plants. Without plants

there would not be a world of animals. Therefore, in her infinite wisdom, Mother Nature made plants easy to ‘catch.’ Had it

been in reverse and plants ran like cheetahs while animals were stuck to the ground like roots, the animals of such a strange

world would not have had much of a chance. To compensate for this lack of mobility, Mother Nature blessed the plants with

numbers. Hopefully, there are more grasses than cows, for what would become of the poor cattle if the reverse were true?

Unfortunately, sometimes the reverse is true and cattle do in fact outnumber the grasses. We refer to these rare incidents

either as scarcity, if we’re talking about a single species, or as the ‘loss of biological diversity,’ if we are dealing with an

entire food chain. In these instances, the ecological pyramid overturns and we have a situation where the many chase the

few (Fig. 2). We refer to these predictable events as mass extinctions. An important part of this process is the aging of species,

specifically of species of plants.

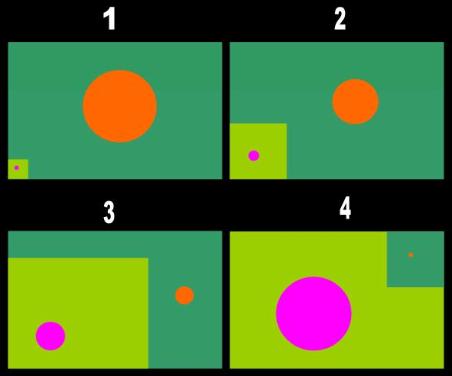

Fig. 2 Speciation: Four snapshots in time |

Fig. 2 Inversion of the Ecological Pyramid The many chasing the few |

a new class of plants develop which have a long-term, strategic advantage over the reigning species. They too discover tiny species of animals carving niches into this new habitat.

old guards are still formidable. The number of species of the old regime decreases as the habitat shrinks, yet the populations of each species expand at the expense of others. Competition fuels Cope’s Law.

old species tied to a shrinking habitat must compete for a smaller piece of the pie. These older species disappear through attrition (background extinctions) and are not replaced with new ones from the same grand lineage. The newcomers are not yet enormous in size, but they are significant in numbers. 4. The new species of plants now dominate the landscape. Most of the old classes of plants

animals that relied on them are about to become extinct, specifically those that developed to the largest sizes. Meanwhile, the new species of tiny animals are ready to take over as soon as the large species of animals of the old guard are gone. The newcomers will grow in size and become the new masters. What decides which of them will grow big is the environment, specifically the climate. Thus, the role of climate is not as most paleontologists believe: to kill species. The role of climate is to determine who will be the next ruler. |

Module main page: Mass extinctions: How the mighty T-Rex really vanished

Pages in this module:

- 1. This page: A mass extinction results when the ecological pyramid overturns

2. The conveyor belt theory of extinction

3. The ecological pyramid overturns: a case study

4. A brief history of homosexuality

| You think that humans are the only ones that get pissed about lousy economics? |