- ________________________________________________________________________________________

- Last modified 09/27/08

- Copyright © by Nila Gaede 2008

| The ecological pyramid overturns: a case study |

| Adapted for the Internet from: Why God Doesn't Exist |

The basic food chain consists of three trophic levels: primary producers (plants), herbivores, and carnivores. In a healthy

or ‘normal’ food chain the higher level typically consumes 10% of the biomass of the level it feeds on. Drastic changes to

these proportions lead to instability. We can expect the animals which depend on a source of food that is rapidly

diminishing to run into a lot of trouble. The fossil record should then show a unique ‘conveyor belt’ pattern when a grand

class of plants comes to an end.

Visualize now the sub-system T-Rex – Triceratops – Cycadeoids some time in the Late Cretaceous (65 mya). The

Triceratopses have grown in number because after millions of years they have finally managed to overcome pernicious

diseases. They are not only more numerous, they are also larger and therefore hungrier. They had to develop size (and

appetites) in response to their ongoing war with their enemies, the T-Rexes. The two species have been around for some

time and have gradually adapted to each other. Only this explains why they are both so formidable.

Unfortunately for the ceratopses, they have grown big and numerous at the wrong chronological moment. Just when the

mighty herds are expanding in numbers as well as in size, the angiosperms have grown from lakes to oceans while the

forests of Bennettitales have shrunk from seas to puddles. The rapidly radiating meadows of angiosperms have converted

the once lush forests of cycads and cycadeoids into pitiful islands. The last terrestrial dino herbivores in this region are

unwittingly trapped in shrinking islands (Fig. 1). They have trouble finding food and limit their populations accordingly

through density-dependence mechanisms.

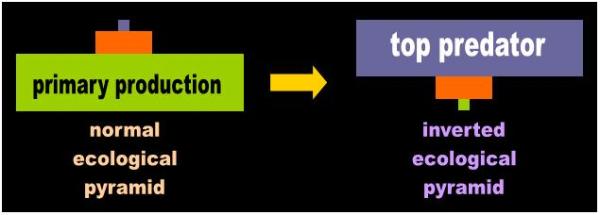

Fig. 1 Eco Pyramid Inversion |

| A normal ecological pyramid is structured so that a given level is about 10% of the one it feeds on. Typically, a carnivore lives by eating herbivores which feed on plants. Towards the very end of the life of a category of plants this process is reversed. The ancient species of plants are crowded out by new breeds and devastated by the animals that feed on them, which have now grown large and numerous. The ancient plants are attacked from both ends: by incoming plants and by the large animals that feed on them. The island shrinks, and the animals that depend on these plants are fated to disappear with them. |

The most compelling evidence for the ecological pyramid theory is what is about to happen to Man. If, as I will show next,

Man cannot avoid the collapse of his carrying capacity despite having super-intelligence and the ability to see ahead, we

must conclude that this is the only intrinsic extinction mechanism that no other species could have avoided either. We

can do something about an asteroid that decides to attack the Earth. We can do nothing about our economy.

| Look! Please try to understand. There was this horrific scientific accident and, to make a long story short, I am not a part of your food chain. |

Module main page: Mass extinctions: How the mighty T-Rex really vanished

Pages in this module:

- 1. A mass extinction results when the ecological pyramid overturns

2. The conveyor belt theory of extinction

3. This page: The ecological pyramid overturns: a case study

4. A brief history of homosexuality

Fig. 1 |

At some point there has to be a strategic crossover. The cycad/cycadeoid to Triceratops ratio locally dips below a critical

level and the unwitting animals are in deep trouble. For them, it happens overnight, although they may have an intuitive

feel before this crucial marker that they have difficulties finding food. Now the process goes into fast forward. We have

the many feeding on the few and observe a rapid overturning of the local ecological pyramid (Fig. 2). The archaic

gymnosperms are slaughtered left and right.

Will the Triceratopses switch diets at the last moment, from cycads to grasses?

Well, do you think you would begin eating tree leaves and weeds if you cannot find hamburgers and French fries around?

Would you have ten children under these conditions?

Meanwhile, the T-Rexes have also expanded demographically in proportion to the population of Triceratopses. This gives

the plants a respite, but it is too little too late. The more versatile, upwardly mobile angiosperms are choking what's left of

the empire of the gymnosperms. A cycadeoid is attacked by a hungry triceratops, and the versatile grasses squat the

property before the beleaguered gymnosperm has a chance to leave descendants. Soon the cycadeoids are all gone.

The Triceratopses are gone. And the T-Rexes are gone. What remains behind are the members of the new order: the

angiosperms and the tiny animals that have carved a niche in this expanding jungle and who are unaffected by what is

going on in the world of giants above. The incoming species are slated to be the rulers of the Cenozoic. This sequence

faithfully reflects the record. An impact winter would have instantly devastated all species in the same proportion, and

this is not at all what we observe.

| When a broad category of families comes to an end, the animals that developed a relation with them for thousands of years cannot suddenly change their diets at the last moment. Unfortunately for them, they have had ample time to acquire immunities to common diseases and begin to multiply. As the herds expand in both numbers and size (Cope's Law), the lush forests and beds contract. At some critical point we have the many chasing the few and the entire system collapses quite suddenly. This phenomenon occurs in the seas as well. The primary oceanic production consists of phytoplankton. All aquatic animals ultimately owe their livelihood to these plants. |