- ________________________________________________________________________________________

- Last modified 03/05/09

- Copyright © by Nila Gaede 2008

1.0 A brief demographic history of the Neanderthals: How the species grew old and conquered diseases

Neanderthals appear in the record following the decline of H. heidelbergensis. This vibrant species of hunter-gatherers

evolves over a period of about 400,000 years and achieves its final form perhaps 130,000 years ago. Neanderthals either

diffuse into Europe or evolve in situ from H. heidelbergensis. They make their last stand about 30,000 years ago in sunny

Spain, the Balkans, or possibly Israel. They probably never numbered more than a few thousands at any given time.

The first question we should ask is, 'Why did they migrate to Western Europe in the first place?'

There are two possibilities. Either Neanderthal evolved in Europe from earlier hominids or he migrated to Europe from

Western Asia. Either way, if he stayed it is because the hunt was good, and if he immigrated, it is because he tracked

large herds into Europe. We must conclude that the continent was teaming with game. The fact that modern man migrates

into Europe a few thousand years later supports the notion of a rich fauna. Neanderthal remains have also been found as

far east as Teshik Tash (Uzbekistan) and Shanidar (Irak), but these bones have been dated in the neighborhood of - 70,000

years, several thousand years before Neanderthal finally went extinct in Europe. Therefore, these outposts lie at the edge

of the Neanderthal Empire and are very likely transitional.

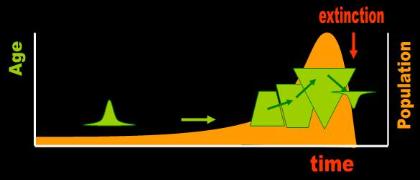

The next question we should attempt to answer is, Why did the Neanderthals halt their expansion (Fig. 1)? If, as Darwin

holds, a species continues to propagate exponentially in the presence of abundant food, why did the Neanderthal

demographic expansion come to an end? In other words, why did global Neanderthal population finally attain ZPG?

Certainly, there were no catastrophic accidents that singled him out among Woolly and modern man. Why did the last

clans stick around and accept their fate? Clearly, if our ancestors followed the herds into Europe, Neanderthal did not

face food scarcity. And if he was outgunned by this formidable, incoming predator, again, why didn't he just move in the

direction of China, across the Bearing, and to America like the mammoths and bison?

| How the Neanderthals really became extinct |

| Adapted for the Internet from: Why God Doesn't Exist |

The day that Neanderthal saturates his carrying capacity, there is a single reason the box of ballons doesn't expand:

Neanderthal does not migrate. He will now spend the rest of his days on this enormous island. The demographic

expansion was brought about by a series of interrelated factors, including immunity to diseases and increases in life

expectancy. The population pyramid now swiftly overturns, and fertility rates decrease during this phase due to

economic pressures. Once the pyramid inverts, there are even fewer incentives for Neanderthal to migrate. In a

seminal experiment, Calhoun (1962) demonstrated what happens when animals are stranded on an island. Their

population stagnates at a low density. In a similar manner, Neanderthal was caught stranded in Europe. There was

enough game locally, so there were no pressures on him to migrate, at least not for long distances. It was probably

easier or culturally more acceptable to conquer territory from rival clans or to form de facto alliances through marriage.

The more or less settled life and the abundance of game, coupled with increasing immunity to diseases contributed to

the overturning of the global Neanderthal population pyramid. The Neanderthals had become 'urbanized.'

4.0 Conclusions

The entire history of the Neanderthal Empire can be likened to a tide. A wave sweeps the beach leaving behind isolated

puddles, all of which are destined to dry out. As a young and vibrant species, the ancestors of the Neanderthals furiously

penetrate Europe, unimpeded, following the herds. The thrust is fueled by an arithmetic demographic expansion kept low

by disease and pulled by an abundance of prey. This lengthy period must and does come to an end. As the migratory

phase comes to a close, the Neanderthals enter their Middle Ages and begin a life quite different than the one lived by

their forefathers. The pioneers become colonists; nomadic ways are traded for semi-nomadic and eventually sedentary

lifestyles.

- Once the Neanderthals experience their geologically brief Golden Age, the crucial parameters are in place to guarantee the

extinction of the species. The age of the population has drifted. A significant fraction of the members are now fulfilling their

natural lifespans and, in this harsh environment, the young must pitch in to support them. There is no longer as much room

for children as there was before and the birth rate begins to drop until it grinds to zero. The clans hold their ground,

sometimes gaining, sometimes losing, but in the end the pool dries up. The great wave is now gone and what remains

behind are puddles destined to dry out.

Thus, Neanderthal reached his maximum geographic extent alone without the help or hindrance of anyone. Aging is the

only intrinsic mechanism that a species has and which prevents it from expanding further. Be forewarned. Aging is lethal.

It kills.

The famous 'experts' of anthropology who suggest that disease was the cause of extinction of Neanderthal, Woolly, or

other species have failed to grasp the basics. The longer a species lives, the lower the chances of dying of disease. Even

assuming that a new disease appears in the horizon, we observe that someone always survives, especially if we're talking

about low-density hunter-gatherers. Viruses and bacteria have absolutely no chance of wiping out a species in the wild.

Anyone who proposes disease as the cause of extinction should be kicked out of science. By this I am not alluding to

whether the last Neanderthal caught a cold and died of pneumonia. I am referring to disease in the context of a natural

mechanism that reduces a population from its historically maximum peak to extinction.

Age structure is such a crucial, quantitative parameter applicable to extinctions that it is perplexing that not one

paleontologist or biologist even alludes to it. The decline in population is an unavoidable mathematical construct of

aging. As the population of a species expands, it gets older. As it gets older, the percentage of individuals in the

reproductive age bracket inevitably decreases. The result is a drop in the birth rate. A drop in the birth rate leads to Zero

Population Growth (ZPG). When a species attains ZPG as a result of aging, there are no further pressures for expansion

(i.e., migration). Hence, the reason Neanderthals finally settled down and stopped expanding had nothing to do with

physical or perceived barriers. It had nothing to do with Cro-Magnon. It had all to do with internal demographic stagnation.

However, I said that Man will vanish in a mass extinction rather than in a background extinction (population pyramid

overturn). A mass extinction claims the last of a long dynasty of top predators. Neanderthal was the top predator of his

age, but he was not the last hominid. That honor and distinction falls on us. In like manner, Albertosaurus was a top

predator before his cousin T-Rex came around. Both were the top predators of their respective epochs, but it would be

the more formidable and streamlined T-Rex who would close the show. A mass extinction involves the overturning of

the demographic pyramid of plants. This leads to a rapid decline in the populations of the animals that are dependent on

them. It is when the carrying capacity crashes that a mass extinction ensues. A mass extinction results when the ecological

pyramid overturns.

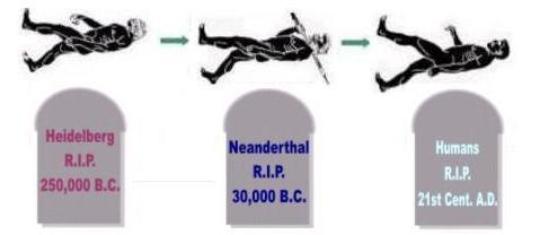

The first strong bit of evidence that we find in support of the 'species aging' argument is that Neanderthal was chronologically

older than modern man. By strange coincidence, it is always the archaic species of plants and animals that tend to die first in

both background and mass extinctions, a feature difficult to explain with extrinsic agents. Neanderthal dates to anywhere from

400,000 to 600,000 years ago. Man appears no sooner than 200,000 years ago. This should raise a flag. If we were standing at

the time line one million years ago, we should be able to predict that Neanderthal will die sooner than Man like your father or

grandfather should die sooner than you (Fig. 4). In fact, Heidelberg was older than Neanderthal by several 100,000 years and

by strange coincidence disappears before Neanderthal.

Is the idiot of Anthropology now going to suggest that Neanderthal and Heidelberg intermarried? Or was it that Neanderthal

annihilated Heidelberg militarily with advanced weapons? Crowd him out with technologically superior tools? Devastate him

with formidable crowd diseases? If Man had not come into the scene, would the Neanderthals have lived forever? Did man

deliberately exterminate the Neanderthals to get rid of a competitor? Why don't the lions exterminate the hyenas on the

Serengeti?

Fig. 2 Background Extinction population pyramid inversion Examples: Neanderthal, Woolly, Dimetrodon |

Fig. 3 Mass Extinction ecological pyramid inversion Examples: Inostrancevia, T-rex, Man |

3.0 The Neanderthal pyramid overturns

So let's recap. After many years of exposure, the Neanderthals eventually conquer their invisible enemies and population

density per square kilometer suddenly begins to increase. Having reached a truce with the viruses and the bacteria that

halt their demographic progress, the average life-expectancy increases and the population within most clans expands.

Children which would have otherwise died in their youth live beyond puberty, and the adults now live to an average older

age. The population expansion is checked by neighboring (and also now more numerous) clans. The culture is no longer

nomadic. The Neander-thals have now been conditioned to a sedentary lifestyle for hundreds of years. Therefore, the new

generations coming out of the wombs do not think about migrating to distant lands to reduce the pressure of scarce

resources. Instead, they stay, hunt in the grounds of their forefathers, fight their neighbors, and care for the weak and old.

The sedentary life brings with it higher density. At some point, the Neanderthal empire reaches its maximum extent, and the

species is caught stranded on an enormous island. However, the island is not shrinking. Mastodon and bison are still doing

fine. It is Neanderthal alone who is in trouble.

One fine day, the global Neanderthal population crosses a new milestone. The average age of the population gradually rises

and the demographic pyramid overturns. Deaths begin to outnumber births. The global population is imploding. Density is

declining.

The demographers and ecologists have been educated to repeat like parrots that when the population drops below the

carrying capacity, shortly after it recuperates the numbers and saturates the carrying capacity again. This is known as the

S-curve. There is no provision for extinction in the S-curve. Supposedly, the species continues to have a constant population

for the rest of eternity as long as resources remain constant.

This is absolute nonsense. The demographics of a species is affected by more factors than just environmental resources. A

quick and dirty thought experiment puts this in perspective and summarily debunks the short term S-Curve everybody lives

with today. I take 1000 humans and provide them with abundant food. After 10 or 20 years we verify that instead of growing

exponentially, the population has dropped to 500. What happened? Well, I forgot to tell you that they were all males! Or

maybe all of these humans were older than 60! Predictably, some died and no new ones came into this world. Hence,

numbers alone tell us nothing.

My point is that it makes no sense to talk about demographic quantities without factoring qualitative factors such as age

composition and location of the species on its time line. If all the women in the world today were over the reproductive age,

we would be witnessing the last generation of humans on Earth. This enormous yet infertile population would inexorably

be extinct in a few years. Likewise, if a species has been around for millions of years, we can also predict that it is soon

going to die. It is not the same to be a young species with few members chronologically at the start of its demographic

history than a numerous, old species which has grown immune to heretofore fatal diseases.

And there is one more density-related factor: finding a suitable mate. Imagine being young and not finding anyone to marry

in a radius of five hundred miles. Or perhaps you cannot find someone suitable to marry at all. If the Neanderthal population

began its decline 5,000 or 10,000 years before they finally vanished, the population must have gradually gotten older. The

old people were crowding out the young. There were no resources to feed baby because adolescents still had to feed

grandpa. The longer grandpa lived, the more a new arrival was postponed. Some generation had to pay the piper. There

had to have come a time when the young had trouble finding suitable mates.

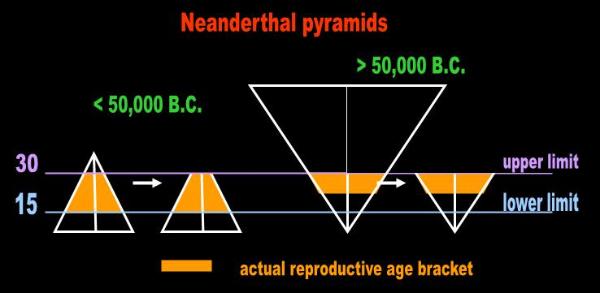

So let's analyze the famous S-curve and see if it behaves the same way when the population pyramid is overturned. A young

species is characterized by a pyramid with an apex pointing upwards. This pyramid can recover from a sudden crash. For

example, our own 14th Century had a 'young' pyramid when the black plague swept through Europe. Although one third to

one half of the population died, Europe recovered the numbers within two centuries. A population that has grown old and is

about to become extinct is characterized by an apex that points downwards. An 'old' pyramid has no ability to recover from

a crash. Are the surviving adults suddenly going to start reproducing like rabbits again just to fill the void left by their elders?

No. They continue having babies as they have been, which is below the replacement level. The culture is no longer towards

extensive families. The Neanderthal now just worries about procuring food for himself and a few close relatives. For instance,

contemporary urban women are no longer having babies. If tomorrow all the people over the age of 30 die, will the young

girls start putting out children to cover the deficit? Will the majority of adolescents who are accustomed to having no children

or at most one suddenly have 15 pregnancies like their great grandmothers? It's difficult to believe that any species that

adjusts its culture to a low level of reproduction over a period of many years will suddenly re-invent hyper-fertility.

To see why the population will not recover once the pyramid is overturned, imagine that we have a young, healthy pyramid.

There is an accident that wipes out a significant percentage of the Neanderthals. The Neanderthals should have no trouble

making up the numbers because the reproductive age bracket continues to be in the same place within the pyramid (Fig. 7).

Catastrophic accidents affect all age groups in the same proportions. They whittle the pyramid from the side.

Now imagine that the population has increased and become old. The pyramid is inverted and is 'unhealthy.' Adults are more

numerous than adolescents which are more numerous than toddlers. The reproductive age bracket is squeezed The upper

limit continues to be the biological limit of 30, but the lower limit rises to 20 or 25 for economic and cultural reasons.

Adolescents postpone birthing for several reasons. They can't find suitable mates within the aging population. They can't

have too many children because of scarce resources. They have to take care of the old, defend against more neighbors, and

still procure food for the clan. The empire is not expanding, so there are no pressures to have as many children as in the past.

In the old days, the Neanderthal would probably had kidnapped a girl from a rival clan and started his own franchise

somewhere. Now, clan territories are established. A greater percentage of youths stay within the clan and inherit the territory.

Business takes priority over pleasure. One day, the old folks start dying in greater numbers. The pyramid is squeezed from

above. The young adults are sad because grandmother died, but happy that they won't have to work so hard now to provide

for the clan. Will the adults put out more children to make the up the difference? Will the adolescents find suitable mates in

such a bleak, low density environment? It is more likely that most will simply live the remainder of their lives in a more or less

sedentary, childless environment, worrying about number one. The advent of modern man could have affected this process

in its last stages, but is not an essential feature.

Fig. 7 An overturned pyramid cannot revert itself |

| Here are two sets of pyramids. The first set shows a young population. If we eliminate all the old people greater than 30, the shape of the pyramid doesn't change substantially and the young generation can make up the difference in no time. The second set shows a more numerous inverted pyramid. Most people are old. If we wipe out those over 30, what remains behind continues to be an inverted pyramid where adults outnumber adolescents which outnumber toddlers. In the context of geologically sudden low density, the Neanderthals cannot revert back to their old culture of having many offspring. It is no longer few clans which are intermarrying and migrating. Now it is many settled clans with few young individuals in each. The practice of founding new franchises has died long ago. The global population of Neanderthals implodes. At this juncture, carrying capacity is immaterial. Irrespective of the abundance of resources, the age structure and the culture associated with it cannot be reverted in such a short time. If we factor an increase in territorial infighting due to the higher density of clans, it is not a safe time to get pregnant anyway. |

Despite not being directly responsible for aging, all extrinsic agents just mentioned have a negative effect on the average

life span of a species. If a tornado happens to kill a herd of herbivores, from a strictly statistical point of view, the average

life expectancy of that species has mathematically gone down. Of these agents, predators and diseases have a greater

effect on average life expectancy because they act constantly and everywhere at once. The more wolves, the more difficult

it is for the average moose to live to a ripe old age. However, by definition, top predators, have little to fear from hunters

outside their species, perhaps at most egg predation or infanticide. This leaves diseases, the invisible enemies that affect

all life on Earth. Predation refers to a living entity that attacks from outside. Disease is an agent that attacks from the inside.

If T-Rex had any enemies with the potential to cut him down in his youth it was the viruses and the bacteria he couldn't see.

In like manner, top-predator Neanderthal had little to fear from anyone except for the invisible critters that crawled inside of

him. Disease was the only factor that kept the Neanderthals from attaining their maximum life spans throughout most of their

history. But then, if the Neanderthals did not change morphologically in the last 130,000 years of their existence (meaning

that they intermarried throughout this time), this gave them all this time to work on developing antibodies. In fact, the entire

history of any plant or animal species can be described as a long process in which it battles and finally conquers diseases.

It is when a species eventually neutralizes the viruses and bacteria that limit its numbers that population is finally

unrestrained and grows geometrically. Soon after, the species disappears from the record. Its global population swiftly ages

and its pyramid overturns.

Neanderthal certainly was one species that had ample time to develop immunities to microscopic vectors the likes of E. coli.

A popular bacteria endemic to hunter gatherers like Salmonella probably had as much effect on him in his latter days as it

has today on snakes, which is none. In the particular cases of Neanderthal and Man, the cooking of food must have helped

them ward against ancient versions of waterborne bugs carrying diseases such as cholera , dysentery, and typhoid. Fire

enabled both Neanderthal and Man to accelerate the process of aging by creating an artificial method of conquering disease.

It would have taken Neanderthal longer to conquer water and food-borne diseases had he not learned to control this magical

tool. The fact that we have found several specimens with arthritis [5] also lends support to this argument. Neanderthal was

now attaining his natural average lifespan in the wild, which was probably around 40 or 45 years. (By the way, some T-Rexes

also seem to have suffered from gout, meaning that this dinosaur also managed to reach old age.). If all species of plants and

animals struggle against disease and eventually reach an accommodation with them, we have to conclude that after 130,000

years of inbreeding, at some point this hominid developed effective antibodies to battle the diseases that kept his population

in check. We must somehow factor this phenomenon into Neanderthal's demographic history.

It could be counter-argued that predators do not have the ability to develop crowd diseases in the wild because they simply

do not have the required density:

- “ Crowd diseases could not sustain themselves in small bands of hunter-gatherers...” [6]

However, predators are nevertheless vulnerable to viruses and bacteria carried by mosquitoes, fleas, flies, and other insects.

Rabbits 'catch' Myxomatosis in the wild, and plants 'catch' fungal pathogen among other diseases. Not a single living entity

escapes disease.

Predators such as Neanderthal and Man are also vulnerable to crowd diseases developed by herd animals:

- “ Among animals, too, epidemic diseases require large, dense populations and don’t

afflict just any animal: they’re confined mainly to social animals providing the

necessary large populations. ” [7]

- It could also be argued that new diseases fill the vacuum. However, proponents of extinction based on disease have yet

to demonstrate that disease can wipe out a species, especially a low-density, widely dispersed hunter-gatherer such as

Neanderthal. Someone always survives. Nevertheless, what new disease are we talking about? Are we talking about an

existing bug that mutated or about a completely new AIDS-like disease that suddenly appears out of nowhere? Is this

what killed the dinosaurs and the trilobites and the pelycosaurs? Where will we ever find evidence for such proposals?

It is conceptually impossible for a disease to kill an entire species. Even the devastating 14th Century Black Plague left

some people alive.

A species necessarily crosses the ominous arithmetic-to-geometric demographic boundary towards the end of its existence.

This is the period in which it attains its greatest demographic growth. Once the bugs are out of the way, there is nothing

preventing the species from attaining its maximum average life span. Everybody who is born lives to have children of their

own. This is the last stretch along the sigmoidal curve and necessarily leads to ZPG. It also leads to extinction because

density-dependent birth rates begin to operate (Fig. 5). The population of the Neanderthals declined gradually over the

course of perhaps the last 10,000 years of their existence. [8] Fig. 5 is an effort to incorporate all of these features. In the

context of a young population pyramid, the species recovers from a crash and continues expanding. The question is

whether a species can recover and avoid extinction once the pyramid overturns.

Neanderthal became extinct shortly after his population pyramid inverted. After thousands of years of adapting to disease

and gradually building up his numbers, Neanderthal finally reached a truce with the invisible enemies that were restraining

his demographic progress. One fine day, the species we know as Neanderthal suddenly grew old:

- " Adult longevity increased with human evolution, from a ratio of old to young adults

of about 0.12 to 0.4 for Neanderthal fossils, with a particularly dramatic increase in

Paleolithic societies to more than two older adults for each younger adult." [1] [2]

Hawkes and O'Connell argue that it is more unlikely for the bones of older people of the farthest past to be preserved as well

as the younger bones from the same epoch. Therefore, there should be a bias in favor of older individuals as we approach

the Neolithic, and this is the reason for these results. [3]

I am not persuaded by their arguments. Assuming this were true, it is unlikely that this would account for the observed 2 to 1

difference.

However, a more fundamental problem of their criticism is the misconceptions the establishment still lives with that:

- " A stable population grows (or declines) at a constant rate, but the fraction of the

population in each age class remains unchanged. Because population growth

rates are exponential, they cannot depart very far from zero for any length of time.

Charnov’s (1993) model explaining the invariant relationship between average

adult life span and age at maturity in mammals is based on this demographic

foundation. In any population that maintains itself over time, the rate at which adults

die cannot be greater than the rate at which individuals mature to adulthood." [4]

- Exactly what they mean by 'stable' is unclear. What is clear is that Neanderthal disappeared. Therefore, he could not have

had a 'stable' population (whatever that means). The rates at which adults died had to have exceeded those who were

maturing at some point in the history of the Neanderthals. The fraction of the population in each age class of a species

whose pyramid has overturned does not remain unchanged! Nature tends to whittle the old from the pyramid. This

process necessarily happens in a faster geological period of time towards the end of the life of a species.

Fig. 4 Mother Nature respects seniority |

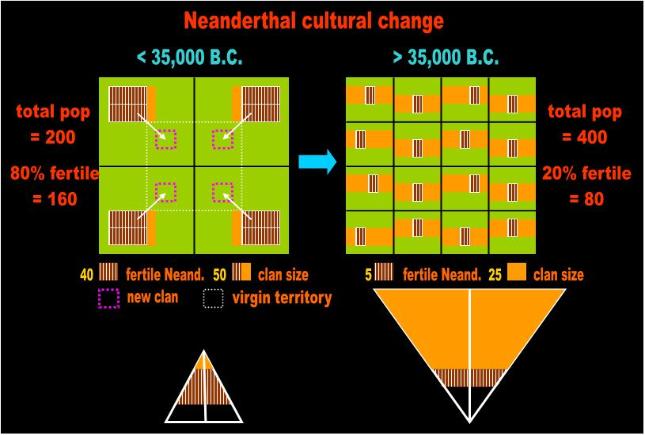

Fig. 6 Conceptualizing Neanderthal's economically-induced cultural change |

| On the left, I have illustrated the old, nomadic lifestyle of the Neanderthals. Each clan is numerous and most members are young. They are far from saturating the carrying capacity, so they migrate and fill niches. On the right, I have illustrated the sedentary lifestyle that developed many moons later. The clans are now less numerous and comprised of older individuals. The young owe their allegiance to the clan. They guard the territory, take care of the old, and provide for the entire clan. Economics has induced a cultural change. This is how the old crowd out the young. Even lions developed prides. Why? Where these big cats always social animals? |

- Module main page: The mechanism behind background extinctions

Pages in this module:

- 1. The three population curves

2. All species eventually conquer the invisible bugs that keep their numbers back

3. Not education, but urbanization causes infertility

4. Urban women have no freedom to choose whether to have a baby

5. An urban woman doesn't have the privilege or need to have a family

6. Density is what overturns a pyramid

7. Urbanization was inevitable

- 8. This page: How the Neanderthals really became extinct

| Heidelberg is an older species than Neanderthal and predictably should have disappeared before him, which he did, Likewise Neanderthal is an older species than Man and predictably should have disappeared before him, which he did. Sometimes sons die before fathers or grandfathers, but in general we should see a pattern where the older species die before the next evolutionary development. Paleontologists and anthropologists routinely give lip service to evolution and invoke extrinsic agents such as climate, disease, and extraterrestrial impacts to justify not only mass extinctions, but background extinctions when it is patently obvious that all species go through a cycle from cradle to grave. |

2.0 How density changed Neanderthal's culture

If we are going to justify extinction on the basis of density-dependent birth rates and a radical curtailing of fertility we

must paint a picture of how Neanderthal's reproductive behavior changed over time, especially near the end of the

cycle of this species. One way of doing this is to attempt to visualize the last days of these creatures.

Let's fast-forward the tape to the end, to the day there was a single Neanderthal left on the planet. How did the last

Neanderthal die? What do you expect to see in the movie?

You may answer that you don't know. Well, that makes two of us. I don't know either. It could have been anything.

What I do know with absolute certainty is that he (or she) was not part of a clan when he died. A clan is comprised

of many individuals. By definition, a Neanderthal that dies all alone is not part of a social group.

So now that he knows where I'm going with this, the devil's advocate takes the discussion to a higher level of difficulty.

What if the entire clan was wiped out simultaneously by someone or something?

This is difficult to believe, but it could have happened. A huge stone rolls down the hill and squashes the last 10

Neanderthals who are playing poker down below. They all die on the same day.

Okay. Now how did the next to the last clan die? How is it that one clan ended up being the last one? What happened

to the others? Were the members of the next-to-the-last clan also wiped out in a single incident by an extraterrestrial

rock? If there were two last clans, why didn't the women from one clan marry the men from the other and jump-start

the race again?

When confronted with the bleak predicament of few members in a species, most people give these pitiful beings few

chances of multiplying ever again. The experts refer to this as the minimum viable population (MVP), a magical limit

from which a species may not recover.

Boyce proposes four mechanisms that prevents a reduced population of animals from coming back: genetic drift,

variability in reproductive growth rates, environmental factors (disease, predators, climate, competition), and population

bottle neck. [9] Unfortunately, MVP blatantly contradicts another 'law' of ecology which states that in the presence of

unlimited food resources, a species will expand exponentially. Under this theory, it doesn't matter whether we end up

with Adam and Eve because these two individuals will repopulate the Earth all over again. The experts live with these

irreconcilable ideas and either don't face their contradictions or fail to identify them. Either a species will always recover

or it dips below a point from which it may not recover. Mainstream 'science' cannot have it both ways.

My version of MVP requires that we understand where the species is in its demographic history. I will argue that a species

that is young can recover whereas one that is old will be doomed to extinction.

As long as the clans were still migrating, the entire empire as well as each territory would have tended to grow through

time. If the extent of the Neanderthal empire finally reached a limit, it is because towards the end of his cycle Neanderthal

changed his habits and adapted to a new culture. Neanderthal was no longer a nomad, but had by then come to terms

with a sedentary way of life. Once he found a cave and abundant game, Neanderthal had no justification to continue

migrating long distances. (He was built like a weight lifter and not like a long distance runner, remember? But actually,

the nomad/sedentary argument applies to any species, even bacteria!) All species sooner or later stop migrating, especially

a hunter-gatherer who comes across an oasis. Hunter-gatherers don't migrate for the hell of it! For instance, the ancestors

of contemporary lions used to be migrants, but now these cats have planted their roots on the savannas and grasslands

of Africa. [10] The lions will travel no more. It is on the Serengeti where they will make their last stand. Therefore, the

demographic history of any animal species has to incorporate this final, sedentary phase as well. A species must eventually

settle down in a given region and die there. Migrants don't become extinct. It is sedentary species which become extinct.

Visualize now an early Neanderthal pioneer tracking a herd. One of his descendants eventually becomes the patriarch of a

clan. The group settles in a region with abundant game, and protects its vital resources from nearby clans through the force

of arms. Several of these clans form a de facto colony. The clan was to the Neanderthals what the tribe was to the American

Indians and the nation to contemporary Man. The clan marked its hunting territory and defended it against neighboring

clans. Initially, with low density and abundant game, territoriality was perhaps not such a big issue. One clan migrated within

a large area and now and then came across and encroached upon another clan's estate without anyone noticing. In the

context of a rich fauna, space was still not a pressing issue.

Fig. 6 illustrates this initial low density scenario. In this example, the colony is comprised of 4 clans each comprised of 50

members for a total of 200. This is a young species that still has not conquered diseases. They have a high capacity to be

fertile because most members are in their reproductive years. We will assume that 80% of each clan can produce children,

40 individuals per clan. A member of a clan can elope with or kidnap a girl from another clan and start his own franchise.

The parent clans tolerate the new neighbors because the blood lines run through both of them, because there is still quite

a bit of land, and because game is abundant. Perhaps the union brings the two clans together. Territoriality is not too

pressing a factor in the presence of abundant game. The Neanderthals have not yet saturated the carrying capacity.

- Now let's run the film fast forward. Many moons later, there are 400 individuals divided into 16 clans, each comprised of 25

individuals. There are several reasons why the clans have become smaller. Locally, they've lived long enough to conquer

endemic diseases. Only 5 out of 25 individuals (20%) per clan are now in the reproductive age bracket. The reason for this

is that the population pyramid has overturned. Having a baby is no longer a matter of choice, but is dictated by the

economic situation. Density dependent births set in, and we follow standard rules of balloon ecology. Infanticide is now a

more common practice. If a baby is born at the wrong time, he or she is sacrificed. The new generation of adolescents are

not at liberty to go and kidnap a lassie and begin their own clans because there is not as much room for expansion. We

are now operating near the limit of the carrying capacity. To make matters worse, the clan elders have arthritis or are

maimed or have lost their teeth or the ability to run and kill game. The young stay within the clan, defend it, hunt and

provide for the entire clan (which is now a full time job and takes up most of their time). The old folks are in effect crowding

out the new generation. Before the clan member decides to have another baby, he has to provide for the elders. This is a

different lifestyle than the one lived by his forefathers. The young, adventurous pioneer has given way to the sedentary

hunter. The Neanderthals have changed their socio-economic culture. They went from small families, to clans, and now to

solitary individuals. The Neanderthals have grown old.

At some point in this chronology, the Neanderthals must necessarily begin to die at a faster rate. Birth rates are down and

death rates are up. This trend conduces to extinction unless it can be reversed. The massive dying of old folks must cause

quite a bit of psychological trauma on the society as a whole. You are no longer seeing babies die as in the past. Now it is

the fathers and mothers who are dying en masse.

Does the young Neanderthal fill the void with babies?

No. The culture has changed. The young generation has learned not to have children. They will not put out babies simply

because grandfather now died. The prevailing behavior among this generation consists of having fewer children, procuring

food for all, and taking care of the sick and ailing. The Neanderthal has changed his behavior. He doesn't have as many

children as his great grandfathers used to. He is not a roaming pioneer, but a sedentary hunter and policeman who has

inherited a territory. His duty is to protect it, not to abandon it. His allegiance is to the clan. His responsibility is to protect

the territory and feed and take care of his elders. It is not the same as in the old days when perhaps 10 young Neanderthals

brought down a woolly mammoth and ate it themselves. Now it is fewer able bodied men, say 5, and they must feed 20. A

child would only be another mouth to feed. So the Neanderthal postpones having children or widens the gap between

them because of economic reasons. When the elders finally die, the adult Neanderthal does not hurry to fill the void with

children because he has now settled into a new lifestyle. On the one hand, it is easier to feed a smaller population. On the

other, he already has one or two children. The next generation is definitely smaller. They grow in a relatively childless

environment too and for the same reasons. We have a world of more adults than toddlers. Once the population pyramid of

a species overturns, it is not nearly as easy to fill a demographic void.

Did the Neanderthals always live in clans? Did they always hunting in groups? Did they ever take care of the old. Was there

a time when they were solitary hunters?

Well, were the lions always social animals, living their lives in prides? Did these large cats always live on the Serengeti plains,

or did they migrate to Africa? Did ants always live in colonies? Did wolves always hunt in packs?

Animals are not only capable of changes in their behavior over time, but they also go through different types of families over

their long history, sometime forced upon them by the circumstances. For instance, if a disease wipes out the pride and leaves

two females, they will necessarily have to tough it out on their own for a while. Their family unit is no longer the pride. Indeed,

some young females and all young males leave the pride. The adolescent lion has no choice but to take over a rival clan. A

lion living all alone in the wild is as good as dead. He has a short life span, must expend energy all day long just to stay alive,

has no sex, and leaves no descendants. It's a lousy life without a pride. To make matters worse, if the lion encroaches on

some other lion's territory, which he invariably does, he is attacked, driven away, or killed. No trespassing is allowed! Keep

out! A lion that leaves his pride must at some point confront the king of another. There is no room for both of them in nature.

The worst enemy of a lion is another lion. What this shows is that a given species may go through different family types

throughout its history, but more significantly, that family types evolve.

What I'm getting at is that the last Neanderthals, maybe the last 100 or 200 ever in existence were no longer part of a clan.

The day the last Neanderthal died, the clans had already disintegrated long ago. All that remained were scattered, lonely

individuals roaming the plains and taking care of their own needs. They weren't interested in having children. The density

was so low that they probably had little chance of finding a suitable mate anyways.

The Neanderthal family undoubtedly changed throughout the cycle of this species like it does for so many other species. In

their heyday, the Neanderthals lived in scattered colonies comprised of several clans. Each clan marked its hunting territory

and patrolled it. The worst enemy of a clan was another clan. It couldn't have been otherwise. Hunter-gathering is founded

on scarce resources. The clan was the country, the unit to which a member owed its allegiance. We have to believe that if

the global population of the Neanderthals receded in the last 10,000 or so years of their existence, it was because their death

rate exceeded their reproduction rate. As the pyramid overturns, there is less of a chance to mate with someone far away,

more so if this is naturally an enemy and more so if the Neanderthals have become more or less sedentary. Once a wild

animal becomes 'domesticated' it is difficult for him to revert to the wild. We can expect that if a clan had few members

because the elderly died, they would not have had the ability of bringing down a Woolly as often as they used to. They had

to switch to lighter game. All these economically-induced cultural changes work against fertility.

Fig. 1 The Neanderthal Empire |

| The Neanderthals barely migrated beyond Europe. If as Darwin and the establishment hold, a species expands exponentially as long as food is available, the Neanderthals should have conquered the Earth. |

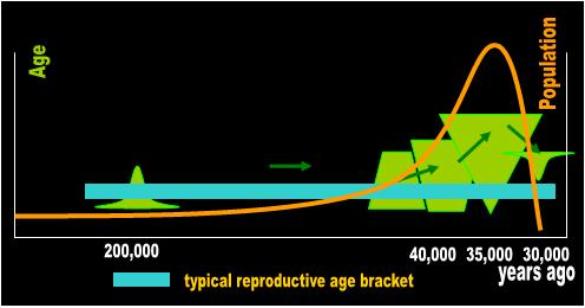

Fig 5 Neanderthal's population pyramid overturns |

| Here is the suggested demographic history of Neanderthal. Many bones of 'old' Neanderthals have been found, some with signs of arthritis, a disease of old age. If it is true that there were two 'old' for every 'young' Neanderthal, the only conclusion that can be drawn is that his population pyramid overturned. After 400,000 years of existence, this species conquered the diseases that kept its numbers in check (not necessarily crowd diseases) and was finally able to attain his natural life-span, which in his case was around 40 or 45 years. Modern man is following exactly in the same footsteps as his long-lost cousin. |

The unsophisticated thinker blurts out the first things that come to his mind: intermarriage, war, or competition, all of which

invoke modern humans. Or perhaps it was disease brought by our ancestors. We terrible humans are the wall that finally

contained our cousins.

I believe that the end of Neanderthal's demographic expansion has to do with aging and with racial senility, two parameters

that suspiciously go hand in hand with density. Racial senility was more or less discarded many decades ago because of

the ridiculous 'predictions' that proponents of senility put forth. I now revive this mechanism with new arguments.

Aging is the only intrinsic mechanism a species has. By 'intrinsic' I mean that aging is not a function of external factors such

as climate, the environment, catastrophic accidents, predators or disease. Aging is something that every individual undergoes

irrespective of habitat, and does so all by himself irrespective of what happens around him. An individual may escape the

weather by flying south or a predator by running north. Not a single living entity can escape aging. Here, I have just

finished arguing that species also grow old. Neanderthal aged when he conquered the diseases that kept his numbers back.

This hominid disappeared all alone in a background extinction (population pyramid inversion) (Fig. 2). In contrast, T-Rex and

others vanished in a mass extinction (ecological pyramid inversion). T-Rex died because he was stranded on a shrinking

island (Fig. 3).